Lessons from Bridging: How to Scrutinize a Private Debt Fund – Part II

“How many red flags are enough to walk away from an investment? One should be enough; anything past one is overkill.” — Harry Markopolos (Madoff’s whistleblower)

Private credit markets can be treacherous. Look no further than the allegations surrounding Bridging Finance. In 2020, a Commission staffer from the SEC said to Reuters, “we’ve had a lot of concerns over private lending.” The source cited the “increased risk in their loans, and room for pricing manipulation” as some of the reasons why the SEC was increasing their oversight over private debt funds. Bridging might be the first “bad apple” in Canada but is not the only one.

Investors and financial advisors must see the concerns of the SEC and the actions of the OSC as a reflection of the risks and pitfalls of investing in private debt funds. The SEC has brought fraud charges against several private credit fund managers such as Platinum Partners, TCA Fund Management Group, and Direct Lending Investments (DLI). The SEC complaints against those managers demonstrate similarities to Bridging Finance and other Canadian private debt funds. Platinum Partners showed an “unbroken string of strong and steady reported performance.” TCA Partners “never reported a down month.” DLI falsified borrowers’ payments to alter the value of the loans.

How to Scrutinize a Private Debt Fund – Part I provided a framework for identifying red flags related to the asset-liability mismatches of private debt funds and risk management practices of private credit managers. Part II will focus on problems arising from the lack of transparency of Canadian private debt funds. This opacity hurts investors and allowed Bridging to conceal its problems for too long.

Transparency

“The manager should be able to show them what kind of things they own in the portfolio and show them how they are monitoring the creditworthiness of that portfolio and how far it’s performing.” — John Wilson, Co-CEO of Ninepoint Partners.

Most private debt funds in Canada, such as Bridging Finance, operate as a black box. Their investment disclosures are opaque. In most cases, investors don’t even know who the borrowers are. Natasha Sharpe once said they couldn’t disclose the borrower’s name due to privacy considerations. She argued that their confidentiality was one of the reasons borrowers selected Bridging Finance.

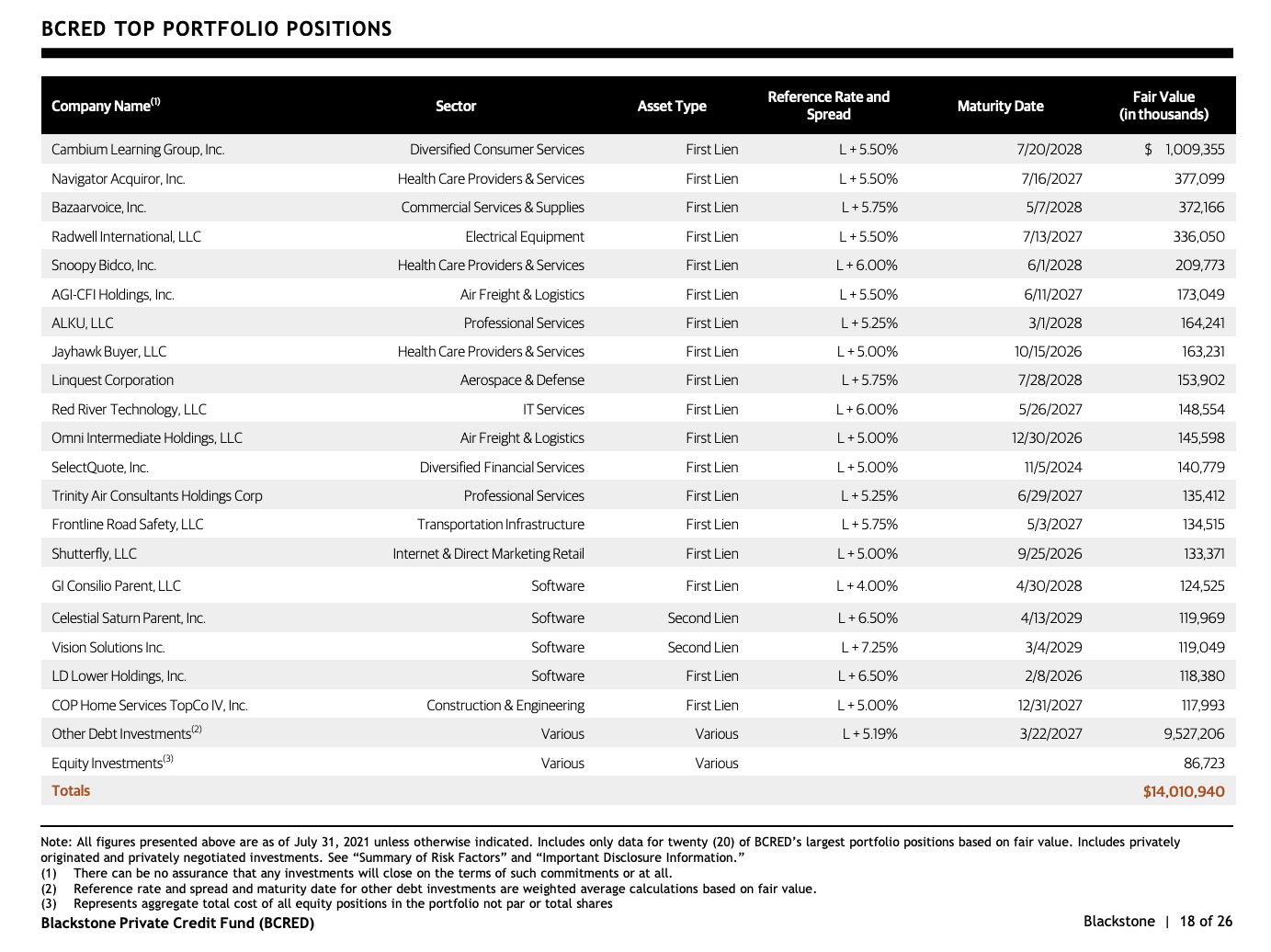

Hiding the name of a borrower is not a practice among world-class asset managers. Blackstone runs a US$ 14 billion private credit fund. Contrary to Canadian managers, they don’t have any problems disclosing their holdings to the public.

Top Portfolio Position for Blackstone Private Credit Fund. Source: bcred.com

The lack of transparency exacerbates an agency problem. There is an asymmetry of information between the investors and the manager. Aligning economic incentives is not enough. Many private debt managers stake their marketing narrative on the claim they never realized a loss – an unrealistic proposition. Any cents-on-the-dollar recovery could undermine this aura of invincibility and their business model. So investors should consider that the manager might have additional incentives that might push him to deceive.

Mr. John Wilson, Co-CEO of Ninepoint Partners and former co-manager of Sprott Bridging Income Fund, said in a BNN Interview, that a private debt manager should tell investors how they are monitoring a loan and how it is performing. Sadly, that is not a common practice in Canada. The lack of transparency undermines investors when they try to know-their-products by understanding (a) the valuations of the loans, (b) the equity positions, (c) the workouts and (d) the manager’s commitment.

Valuations

If managers disclose the borrower’s name, investors can independently gain a sense of the loan’s value. Investors need to understand how private credit is valued. Loans held by private credit funds are just contracts with a net present value (NPV) tied to the stipulated cash flows. IFRS 9 is the standard to value financial assets such as loans.

Some private debt funds say they use IFRS 9 and calculate a fair market value to all their loans on a daily basis. Still, their level of concentration, credit quality and lack of volatility on their NAV say the opposite, resembling Bridging’s posted returns and other red flags.

IFRS 9 states that a financial asset is credit-impaired when one or more events that have a detrimental impact on the estimated future cash flows of the financial assets have occurred. Some of these observable events categorized in IFRS 9 Appendix A are:

- Significant financial difficulty of the borrower.

- A breach of contract, such as a default or past due event.

- Granting concessions due to the borrower’s financial difficulties.

- It is becoming probable that the borrower will enter bankruptcy or other financial reorganization.

To provide a sense of the challenges of assessing the value of a private debt portfolio, take a look at Bridging’s receivership. Since April 30th, 2021, all the Bridging’s funds have been under the control of PwC. After more than four months, the Receiver has not provided a NAV for the fund. They are currently executing a Sales and Investment Solicitation Process (SISP) to let the market discover the value of the fund’s assets.

PwC recently confirmed that Bridging Finance misstated NAV calculations by not reducing the book value of the loans, “including in circumstances in which the Borrower was in an insolvency proceeding or when Bridging was engaged in active litigation proceeding to pursue collection.” Meaning that no write-downs were recorded even when the borrowers hit a wall.

Another example of the challenges while dealing with private fixed income instruments is Greensill Capital, a financial services company that offered supply chain financing (private credit). The company declared bankruptcy and is facing a criminal complaint in Germany. In March 2021, Credit Suisse suspended redemptions and subscriptions in funds related to Greensill. The Swiss bank said, “a certain part of the [fund’s] assets is currently subject to considerable uncertainties with respect to their accurate valuation.”

Some managers even say that investors don’t have to worry about the buy and sell demand fluctuation of private loans. Investors who think the lack of volatility is a good attribute should read Julian Klymochko’s case on why mark-to-market accounting is beneficial.

But the most critical aspect is to determine who values the loan. Even though many managers say they used third parties to value their assets, the honest answer lies in the offering memorandum (OM). In many private debt funds, that responsibility rests with the manager. This creates a conflict since the compensation and reputation of the manager depend on their judgement. The incentives for the manager will push them to avoid write-downs and use the “extend and pretend” scheme.

🚩 Red Flag Watch 🔍

- Check the OM section called “Computation of Net Asset Value.” You will find a subsection describing how they determine the market value of the assets of the fund. The subsection will explain how they assess the value of cash, quoted equities and bonds, derivatives and, more importantly, securities or properties for which no price quotations are available. Bridging’s OM said, “assets for which no published market exists will be valued at fair market value which typically would be cost unless a different fair market value is determined by the General Partner and the Manager.”

- Ask the manager how they value the loans. Even if the manager says they apply IFRS 9 and use a third party to value the loans, independently verify that information. Remember that David Sharpe said on BNN Interview that they applied IFRS 9.

- If the fund has provided concessions by waiving covenants or extending maturities, you should assume that the loan is impaired. The NPV of the cash flows stipulated initially will be affected by those changes.

Equity Sweeteners

As part of their strategy, some private debt managers negotiate equity positions in the companies they lend to. Warrants or options usually represent those equity positions. Giving out a loan and receiving warrants is the equivalent of buying a convertible bond.

Investors should be aware that usually, companies that issue convertible debt can’t access traditional financing due to their perceived risks. If borrowers are willing to dilute their ownership it’s because they have no other option to obtain funds.

When a manager demands a meaningful equity position before disbursing a loan, he signals his conviction that the business will thrive with the proceeds of the credit agreement. But if the company hits a wall and ends in an insolvency proceeding, investors should expect that equity position to be wiped out. In any capital structure, losses will be absorbed by equity investors first.

🚩 Red Flag Watch 🔍

- Understand the motivations of a borrower to accept a dilution of their equity stake. Keep in mind that for a business owner, issuing debt is always cheaper than issuing equity.

- Beware of transactions where a borrower is willing to issue warrants to acquire more than 10% of the company’s equity.

Workouts

Workout is the fancy word private debt managers use to refer to a loan that goes sour due to the borrower hitting a wall. Initiating an insolvency proceeding is a confirmation that the credit is impaired. Many private debt managers downplay insolvencies by simply calling it a restructuring while emphasizing their seniority in the capital structure.

Our previous article, The Myth of Senior Security, addresses the pitfalls of those claims made by private debt managers. Investors must be aware that an insolvency proceeding is a long, complex and expensive process – financed by investors. Those proceedings result from the inability of a business to generate the expected cash flows. If a firm generates less free cash flow than expected, investors should assume the value of their asset has been impaired. The intrinsic value of a financial asset equals the NPV of future cash flows.

As an example of how credit gets impaired when looming with insolvency, we refer to a secured bond issued by the China Evergrande Group (ISIN XS1580431143). The issuer, a property developer from China, is currently facing a liquidity crunch. The Financial Times reported that the company has hired restructuring advisors. The secured bond with a coupon of 8.25% traded at 108% of par value in May 2021. Less than four months after the price hovers around 55%.

Price Chart for Evergrande Secured 8.25% 2022 Bond. Source: bondsupermart.com

If a borrower asks a court for creditors’ protection, investors should expect an impairment to the original loan. The magnitude, implied risk, and the timing of the cash flows will be different than initially stipulated. The NPV of the new loan will be lower than the NPV of the original loan, meaning that investors have suffered a loss.

🚩 Red Flag Watch 🔍

- Verify if any of the borrowers or the fund is part of insolvency proceedings. In Canada and the US, those processes are public. Insolvency Insider provides a valuable database with a summary of the most recent proceedings in Canada. Performing a Google search with your manager’s name and the words CCAA, BIA, Chapter 11, or insolvency will help you identify those cases.

- Beware of insolvencies where a SISP is executed. In many cases, the only buyer of the collateral is the private debt manager itself, as Bridging Finance did with Allied Track Services. This is a signal that the collateral value has been affected and is not enough to cover the outstanding debts.

Commitment

Investors must confirm the commitment of private debt managers to the fund they oversee. Many of them hold external board positions, which distract managers from their duties and responsibilities to investors. In some cases, the principals and employees of the fund managers control the board of directors of many of their top borrowers creating conflicts that might hurt investors.

🚩 Red Flag Watch 🔍

- Perform a corporate record search for the principals and top employees of the private debt manager.

- Beware of managers overseeing multiple funds. As in the case of Bridging, PwC has said that “on occasion the Bridging Funds would transfer positions in Loans to other Bridging Funds … Interfund Loan Transfer were executed at the book cost of the loan at the time of transfer, in exchange for cash consideration of equal value. This financial game allowed Bridging Finance to conceal its losses.

**********************

Investors should be skeptical of financial products that are too good to be true. Financial Advisors need to understand the real risks of the products they are pushing to their clients. Unscrupulous managers will keep pulling rabbits out of their hats to defy reality and deceive investors. They will keep covering their mistakes until the music stops and a lack of transparency about their holdings facilitates this process. By placing more concentrated and riskier bets, it is unlikely that they will recoup the accumulated losses.

Private debt managers are facing a confidence crisis. Today is not the time to promote private debt funds, as Mr. John Wilson did in 2019. He should aspire to lead the industry by adopting best practices that were so lacking with Bridging Finance. Rather than trying to silence his critics, he could start by increasing Ninepoint’s transparency and replicating Blackstone’s practice of disclosing their borrowers’ names to the public.

Disclaimer: This article is not investment advice and represents the opinion of the author.

Sources:

-

U.S. SEC steps up scrutiny of private debt ‘financial games.’ Reuters.

-

SEC Complaints against TCA Fund Management Group Corp, Platinum Management (NY) LLC and Direct Lending Investments LLC.

-

Everything Is a DCF Model by Michael Mauboussin and Dan Callahan.

-

China’s Evergrande faces investor protests as liquidity crunch worsens. Financial Times.

-

Affidavit of Daniel Tourangeau in the case of Bridging Finance.

-

Reports to the Court of PwC as receiver of Bridging Finance.

-

BNN Interviews featuring John Wilson and David Sharpe.