Lessons from Bridging: How to Scrutinize a Private Debt Fund – Part I

“Stay curious, stay skeptical”

– Ken Lester

Many investors and advisors were surprised after a court placed Bridging Finance into receivership. Some investment professionals ignored the warnings and now tell their clients that they are victims of Bridging’s management deception. However, investors and not their advisors are the ones suffering their consequences. The seekers of an enhanced return from alternative investments can avoid further pain by identifying red flags in a private debt fund. Readers of this article will learn to spot some of the potential warning signs in the space.

The promise of a high source of income with low volatility and uncorrelated returns has seduced many, from retail investors to family offices and pension funds. Nonetheless, investors now know the reality of the risk-return proposition and the myth of senior security some Canadian private debt funds offer. The allegations around Bridging Finance have led market participants to think twice before buying or holding units in these funds, while looking closely at their investment strategy.

John Wilson, Co-CEO and Senior Portfolio Manager of Ninepoint Partners, an alternative investments firm that acted as co-manager of Bridging Income Fund until 2018, was asked in 2019, during a BNN Interview, about which points to scrutinize and how to engage in risk analysis of a private debt fund. His answer pivoted around three themes: (a) liquidity mismatch, (b) risk management and (c) transparency.

This article will explore the potential red flags that might arise from analyzing a private debt fund’s liquidity mismatch and risk management practices. A follow-up article will address the issues that come to the surface from the lack of transparency. Readers will be able to identify some of the red flags that can emerge from probing any manager with skepticism.

Liquidity Mismatch

“Make sure that the investments that are being made sort of make sense relative to what kind of liquidity you being told that you have access to” – John Wilson

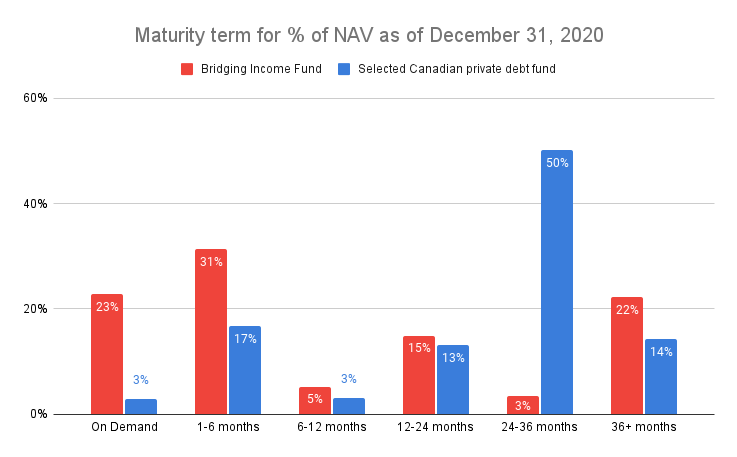

In the interview, Mr. Wilson addresses the historical risk of a liquidity mismatch. He says, “as a manager, we also need to understand what the underlying liquidity of the investments are and match that to the terms that we offer to our investors.” Most popular Canadian private debt funds offer monthly liquidity, but many, like Bridging, have a considerable concentration of their loans maturing after 24 months, signalling a mismatch.

A few months before Mr. Wilson, David Sharpe sat in the same chair with BNN. Mr. Sharpe minimized the risk of a liquidity mismatch by saying, “all of our facilities are demand facilities, so we can get out at any time for no reason.” In reality, it seems that Mr. Sharpe misrepresented the facts.

Bridging’s receiver has demanded payment from its biggest borrower, Alaska-Alberta Railway Development Corp, which then filed for creditor’s protection. MJardin Group, which owes more than $150 million to Bridging, is executing a sales and investment solicitation process of all assets to face their liabilities. The audited accounts for Bridging Income Fund, as of December 2020, showed that less than 25% of the loans were on demand.

The following graph shows a portfolio maturity comparison between Bridging Income Fund and a selected Canadian private debt fund with monthly liquidity. In both cases, the terms of the investments don’t make sense relative to what kind of liquidity you are told you have access to.

🚩 Red Flag Watch 🔍

- Investors should check the OM and ask the private debt manager their targeted term of maturity. Compare that range to the actual portfolio.

- Run a stress test simulating if the fund can stand a 30% net redemption in one year.

- Look for concentrated maturities outside their targeted terms.

Risk Management

“Risk management is incredibly important.” – John Wilson

According to Investopedia, risk management is the process of assessing, managing and mitigating losses. To be pragmatic, we will rely on the risk management framework of renowned hedge fund manager Steve Cohen. In a recent interview, he said he focused on three things to manage risk: liquidity, leverage and concentrations. He explains:

“If you’re in illiquid stuff, that’s a problem. If you’re using too much leverage, that’s a problem. If you’re too concentrated, that’s a problem … If you have one of them, maybe it works. If you have two of them, Oh! Oh! If you have three of them, you are whistling past the graveyard.” – Steve Cohen

Iliquid Stuff

Private debt loans are illiquid stuff. As said by Mr. Wilson, “these are not instruments that trade publicly, and you can’t get your money back on one day’s notice.”

An investor can trade off liquidity for higher returns. But when you face high uncertainty in the possible outcomes of an investment due to their increased risk, you will prefer to have liquidity than not. For example, if you disburse a loan and then realized that the collateral was misrepresented, you will hope for a bid price so you can exit that loan and transfer the risk. That way, Bridging could have avoided holding their loans to Gary Ng, who, according to IIROC, falsified documents to secure some loans from Bridging.

Mr. Sharpe told BNN regarding another troubled loan to Bondfield Construction that they were “happy with that credit” and that they sold it to a family/corporation that “liked the payouts on the assets.” That statement provided a sense of liquidity. In reality, Bridging explained to the OSC that in 2018, an $84.5 million loan to Bondfield was assigned and assumed by an entity controlled by Sean McCoshen, of which only a $59 million repayment has been received by Bridging as of February 2021.

In another transaction, reported by PwC as receiver of Bridging, “three loans from Borrowers related to Gary Ng with a book value of approximately $105.5 million at the time of the transfer” were assigned to an entity in consideration for a promissory note in the principal amount of $43.47 million with interest to be paid at the rate of 1%. No cash changed hands.

🚩 Red Flag Watch 🔍

- Ask the manager if they have sold any loans. Confirm their answer with the audited cash flow statement.

- Be suspicious of non-cash settlements.

Leverage

Even when most private debt funds don’t use leverage, their capital structure, contrary to banks, lacks equity. Banks are the direct competitors of private debt funds. It is hard to think of a sector that is more supervised than the banking industry. Almost every country has a banking authority that closely monitors the lending activities performed by the regulated subjects.

Opposite to a bank that uses its capital as a cushion to protect depositors, a private debt manager’s capital is not at risk. It is not the same for a bank, where the owner’s equity will absorb the losses first until it is wiped out to hurt depositors then. So private debt investors should expect the NAV to tick down when an investment goes sour.

Banking supervision is an evolving task. For example, after the Great Financial Crisis, the Dodd-Frank Act was passed, IFRS 9 was implemented, and Basel III was introduced. Many laws, standards and regulations have been established with the sole purpose of protecting depositors and demanding more equity to assume potential losses that are inevitable in the lending industry.

🚩 Red Flag Watch 🔍

- Investors should know that the losses arising from a bad loan will be shared among all investors, including the managers if they are invested in the fund. It is not comparable to a bank where the owners will first absorb losses.

- Unitholders should understand how management is compensated.

- Beware of related party transactions to subsidiaries, portfolio companies or related investments.

Concentration

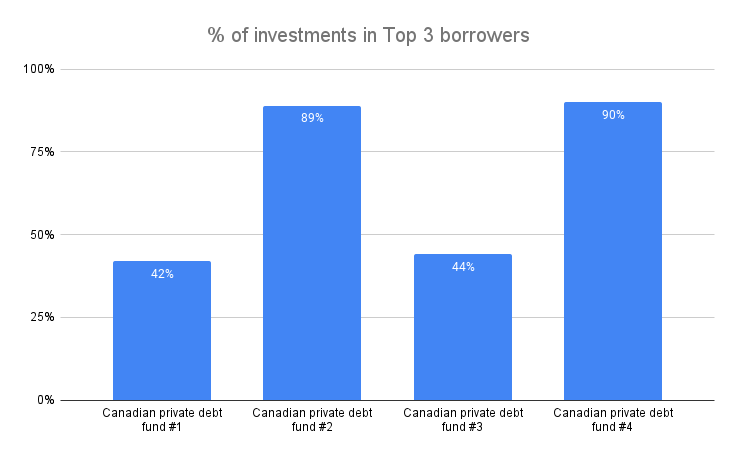

Many Canadian private debt funds run a very concentrated portfolio. The following graph shows the concentration of the top three borrowers for a sample of funds run by Canadian private debt managers as of December 2020.

Investors are at risk to such a concentrated portfolio in illiquid stuff as private debt loans. Even more, when the risk profile of the investments is high, and uncertainty increases the possibility of realizing a loss. Limiting the vulnerability to a single borrower is why banks worldwide have many restrictions about the total exposure to a counterparty.

In some cases, one of those top three holdings started as a small position but then grew like a snowball. When the borrower hits a wall, these managers can decide to waive covenants, capitalize interest payments, extend maturities or increase the size of the credit facilities hoping to turn around the business.

For example, from January 2017 until May 2019, Bridging amended 14 times their credit agreement with Hygea Holding increasing the credit outstanding on every occasion. The same has happened with other private debt managers who have adopted an “extend and pretend” scheme. Sometimes a $10 million loan has compounded over the years to a $200 million exposure to an undercapitalized borrower running a loss-making business.

🚩 Red Flag Watch 🔍

- Investors should analyze the concentration of the top three, top five and top ten borrowers.

- Some managers report their positions by facilities where the same borrower may have many facilities.

- Be suspicious when one borrower represents more than 15% of the loan book.

According to Steve Cohen, a private debt funds strategy might work by investing in illiquid stuff. But when they also run a concentrated portfolio, as many in Canada, realizing a permanent loss is a very likely scenario. Somehow, many fund managers have managed to avoid losses. Thanks to Bridging’s events, now investors can know the real risks and take responsibility for the future of their investments.

Part II of this “Lesson from Bridging” will analyze the most critical theme expressed by Mr. Wilson, transparency from where most of the red flags can arise. If Bridging Finance had been transparent, probably their business would not have been viable, and a lot of misery could have been avoided.

Disclaimer: This article is not investment advice and represents the opinion of the author.

Sources:

- Affidavit of Daniel Tourangeau in the case of Bridging Finance.

- BNN Interviews featuring John Wilson and David Sharpe.

- Audited accounts and marketing materials of several private debt funds.

- Inner Game with Steven Cohen (stray-reflections.com)