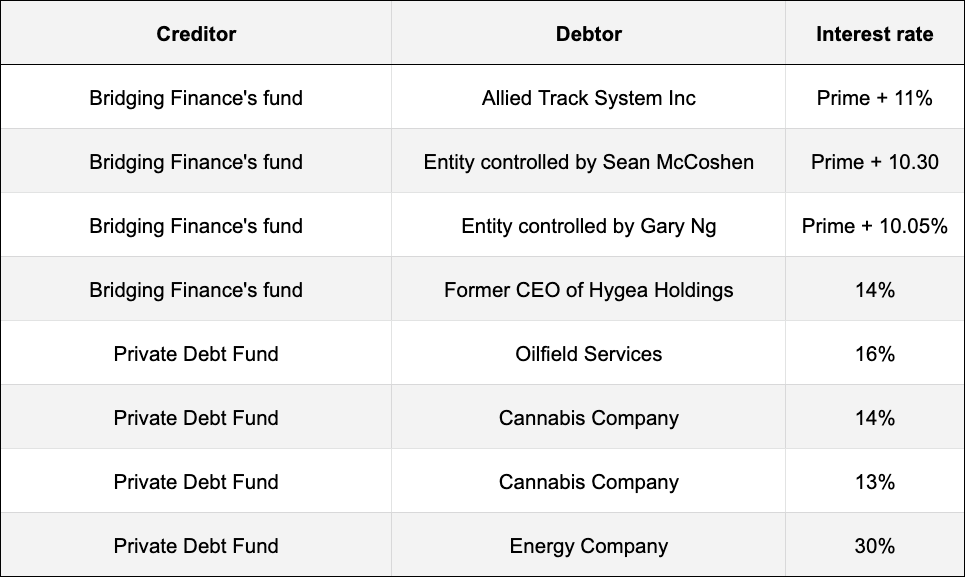

Lessons from Bridging: risk-return proposition of private debt funds.

“It is not reasonable to expect highly superior return without bearing some incremental risk.” – Howard Marks.

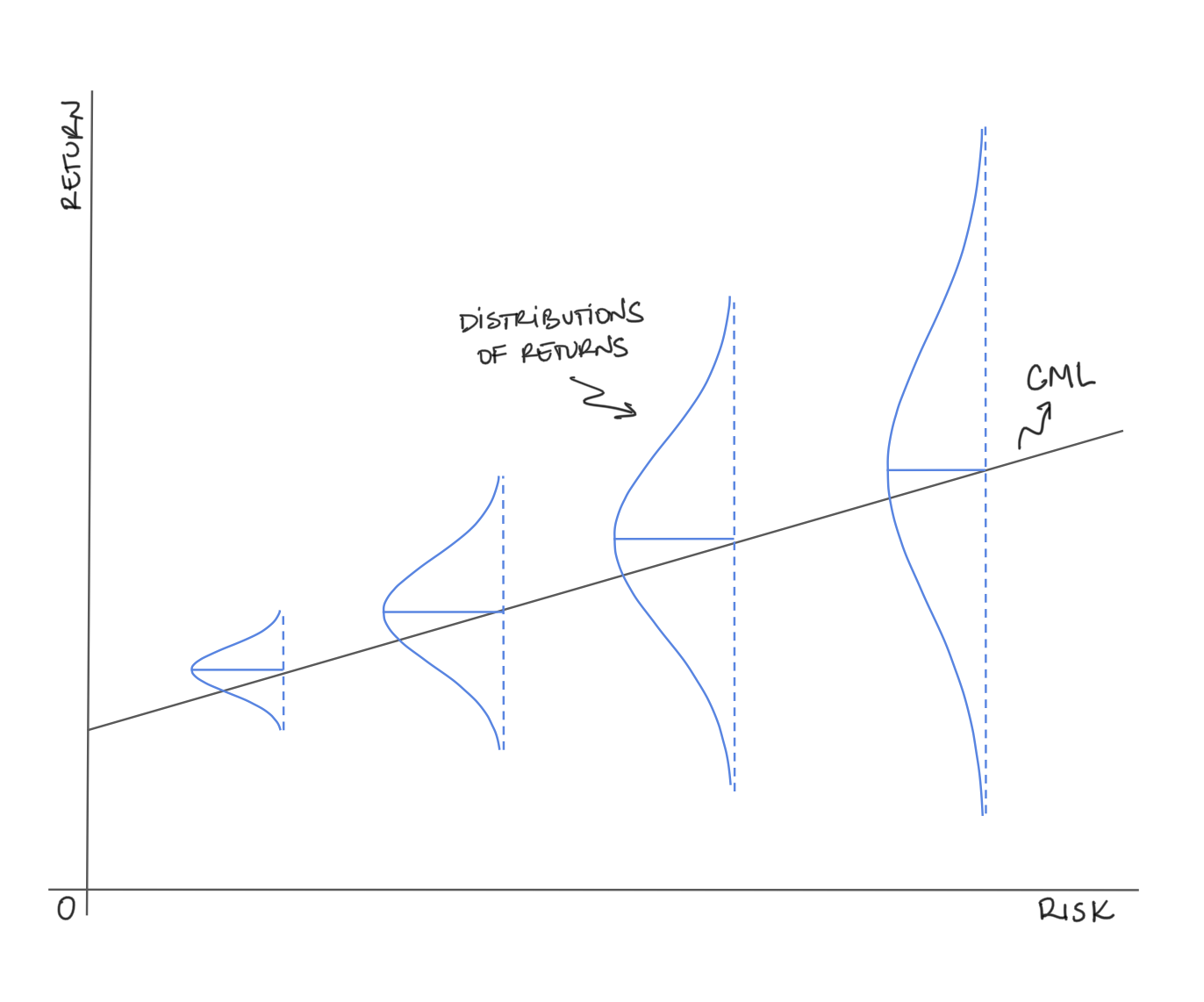

In almost every finance course, students learn about the Capital Market Line (CML). The theory establishes the relationship between risk and return. If an investor wants to increase their returns, they will need to accept more risk. But taking a higher risk doesn’t guarantee a higher return.

To grasp the relationship between risk and return, I refer again to Howard Marks, who presents a modified and more pragmatic version of the CML. He describes his view of the theory as “through the imposition of some probability distributions to indicate that not only when risk increases does expected return increase but so does uncertainty.” The following graph shows his work on the CML

Mr. Marks explains, “the conclusions are obvious from inspection. As you move to the right, increasing the risk: (i) the expected return increases, (ii) the range of possible outcomes becomes wider, and (iii) the less-good outcomes become worse. This is the essence of investment risk.”

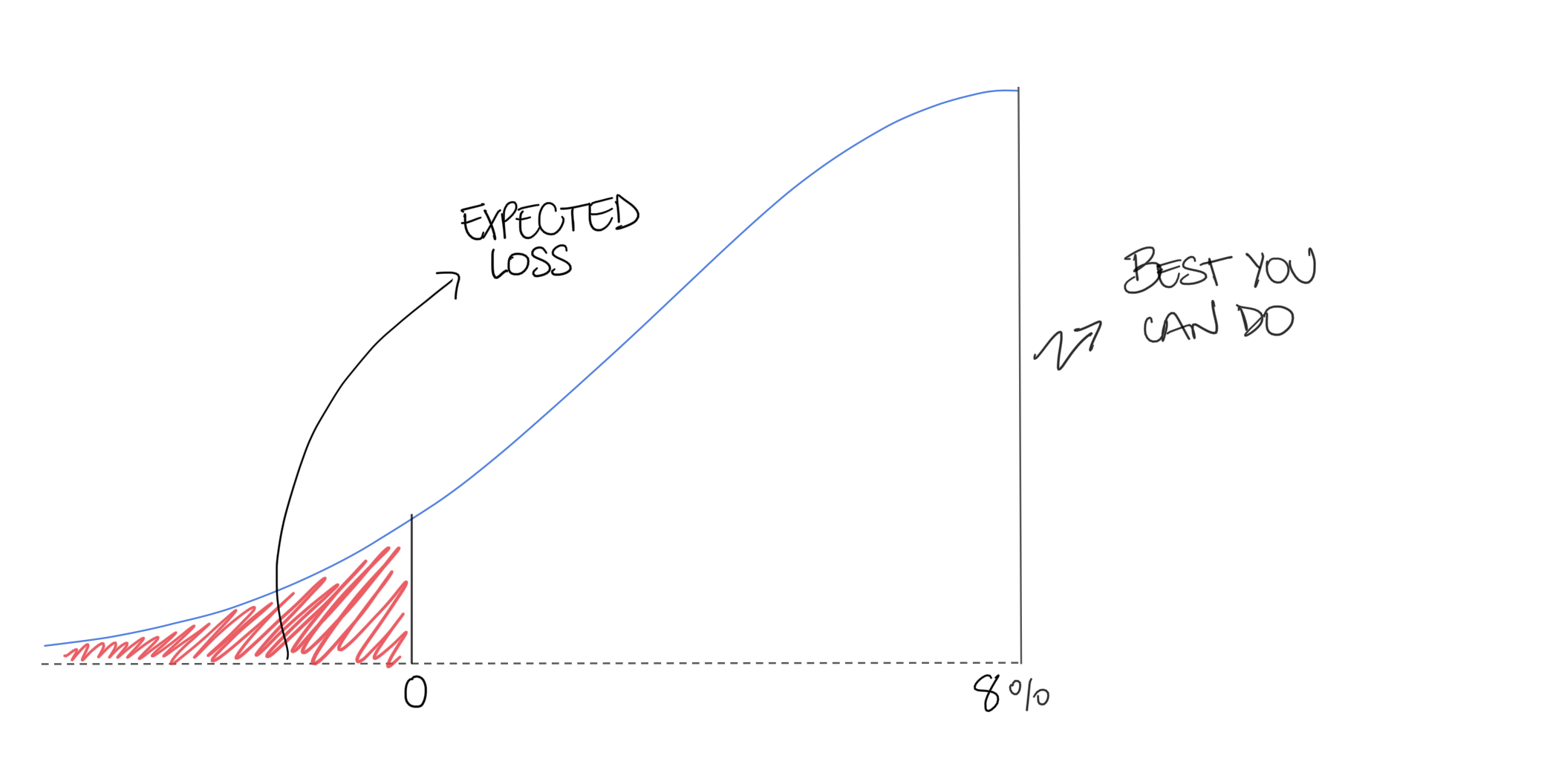

His modified version of the CML applies to all asset classes. However, fixed income securities have a different distribution of returns. As explained by Mr. Marks, “If you buy an 8% bond at par, pretty much the best you can do is get paid 8% at maturity. But there are lots of degrees of failure. You might get 80 cents or 60 cents or 40 cents or 20 cents in a bankruptcy.” The following graph shows an example of a distribution of return for a plain-vanilla fixed-income instrument held to maturity.

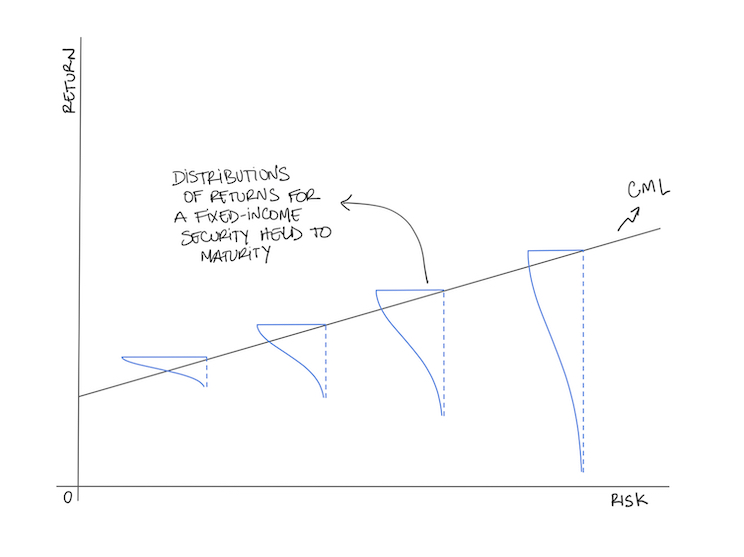

We have adapted Howard Marks’ version of the CML for fixed-income securities. By superimposing approximate returns distributions of fixed income securities, we can better grasp the risk-reward proposition of investing in private debt.

Elroy Dimson, a former professor of LBS, said, “risk means more things can happen than will happen.” The increased uncertainty resulting from higher risk opens the door to multiple scenarios that might unfold in the future. When a loan is disbursed, both parties expect to pay and receive a stipulated cash flow during the contract’s life. If the credit risk is low, getting fully paid is a very likely scenario. But as you increase credit risk, the array of possible outcomes where the creditor doesn’t get fully paid grow considerable.

In the case of Bridging and of other Canadian private credit funds, they have not been able to steer clear from bad loans. Some of the adverse outcomes could be observed when the creditor waives covenants, extends maturities, amends a credit agreement ten times, discovers that collateral didn’t exist, or the borrower ends up in CCAA or receivership. These observable events have a detrimental impact on the estimated cash flows of a financial asset. Thus they are a sign of credit impairment as defined by IFRS 9.

Bridging’s events should be seen as an example of the real risks incurred in the private debt space. Those events should activate our sense of disbelief. Premium returns with no permanent credit losses is an appealing narrative. It has captivated investors seeking to increase returns in a low-interest-rate environment. Now, some of those investors are facing the misery of the real risks of the asset class.

Chasing higher returns means that investors will face higher uncertainty in an imperfect world. Given fixed-income instruments’ payoff structure, the increased uncertainty translates into a higher possibility of a permanent loss. I know some of you might think this doesn’t apply to you since the funds you invest can achieve premium returns because they only invest in senior secured loans, just as Bridging Finance said. In our next article, we will tackle down the myth of senior secured debt.

Disclaimer: This article is not investment advice and represents the opinion of the author.

Sources:

- Howard Marks’ memo titled “Risk” of 2006.

- Howard Marks’ memo titled “Risk Revisited Again” of 2015.

- Invest Like The Best: Howard Marks – Embracing the Psychology of Investing.

- Affidavit of Daniel Tourangeau in the case of Bridging Finance.

- Various press releases and securities filings.